Hey, everyone! Cate here with another QuickTake on—wait, it’s not Tuesday! What’s going on? Yule never guess! Coming to you from Toolhouse Rock Studio, it’s a QuickTake Christmas special. You’re in fir an advent-ure with this jingle single! Please like, comment, and share. #sleigh #takesbough #amwriting #qtwcate

Quiction – “That Place”

Today’s Quiction is entitled “That Place—Or Why I Probably Shouldn’t Be a Children’s Author.”

I had fun with it and hope you will too!

QT 24 – Now You See That, Now You Don’t

QT 24 – Video Transcript and Bonus Info

Welcome back to Toolhouse Rock Studio for another QuickTakes with Cate. Today we get our Harry Potter on with the word “that.”

It’s Christmas morning at Hogwarts when Harry opens a mysterious parcel at the foot of his bed. Inside is something fluid and silvery gray. “It’s an invisibility cloak,” Ron Weasley informs him. Throw it over yourself, and you become invisible—as in this sentence. Do you see where it is hiding a word—the word that ? Twice.

Aunt Petunia often said Dudley looked like a baby angel—Harry often said Dudley looked like a pig

in a wig.

Ahh, here they are.

Aunt Petunia often said [that] Dudley looked like a baby angel—Harry often said [that] Dudley

looked like a pig in a wig.

So which way did JK Rowling write it? Is one way right and one way wrong?

One task of an editor is to delete unnecessary words. Possibly the most hunted word by eager editors is the word “that.” Bryan A. Garner writes, “Those who rabidly delete ‘that’ seem to be overreacting to those who use it excessively.”

So how do we know when to leave it in and when to take it out?

Here’s the magic trick that will help you decide: When a sentence could possibly be misread without the “that,” leave it in. If there is no possibility of misreading, go ahead and take it out.

Consider the possible misreading of this sentence:

Harry found the invisibility cloak, which he unwrapped, felt like water.

Without that, you might read the sentence as follows:

Harry found the invisibility cloak, which he unwrapped…

The word that helps us read the sentence correctly:

Harry found that the invisibility cloak, which he unwrapped, felt like water.

If you do opt to take the word that out of an otherwise clear sentence, remember [that] it’s still there. As JK Rowling tells us when Harry tries to disappear down a narrow corridor, “the cloak didn’t stop him from being solid.”

Oh, and in our original sentence about Dudley, she kept the thats in.

The rest of the story:

Let’s take another look at this sentence:

Harry found [that] the invisibility cloak, which he unwrapped, felt like water.

Without “that” in the sentence, we will at first read “invisibility cloak” as the direct object of the action verb “found” rather than as the subject of a dependent clause. The word “that” signals to the reader the beginning of a new clause.

If you are writing global English, be especially careful not to remove helpful occurrences of “that.” Global English is English that is precise, consistent, unambiguous, and universally readable.

Look for the verbs assume, be sure, ensure, indicate, mean, require, specify, verify, and recommend. Ask yourself whether inserting the word that after these verbs will make the sentence structure clearer. In these instances, the word “that” tells the reader that a noun (dependent) clause follows. (Science and Technical Writing, A Manuel of Style, by Philip Reubens)

QT 23 – The Tale of Benjamin Bunny—Or Is That Tail?

QT 23 – Video Transcript and Bonus Info

Welcome to 2-Minute Tuesday and another QuickTake with Cate.

So which would you select as the correct word in this sentence (all of these are actual words): caret, carat, karat, or carrot?

Benjamin Bunny decided to bring his mother the heaviest _____________ he could find.

Ooh, that’s an answer worth waiting for—or is it weighting?

As an editor, I have to catch errors that grammar and spell check miss. Often writers have no idea that the word they used is not the word they meant, either in meaning or in spelling or both. For example, there’s peak and there’s pique; affect and effect; principle and principal; advice and advise; to, too, and two; bear and bare; due to and do to; regimen and regiment; kernel and colonel; counsel, council, and consul; site, sight, and cite; and the list goes on. And on and on. And that’s the trouble!

Two of the most commonly confused sets of words I see as an editor are lead and led and insure, ensure, and assure.

The noun lead, which rhymes with head, is a soft metal used in pencils and other items. The verb led is pronounced the same way as a pencil lead, but it is the past tense of the verb lead, which means to guide or direct and rhymes with deed. When describing a project on your resume, you would write, “I led a team last year.”

To remember the differences between insure and ensure, use insure for a money-backed guarantee; think of insurance. Use ensure to mean “make certain”—no money involved. “We can ensure that the launch will be successful.” The word assure is a promise given to another person. That person needs to follow the verb. “I assure you that we will finish soon” and “I assured Benjamin Bunny we would return to his story.”

So what is his story? What did he bring his mother? Did he bring her the heaviest carrot in Mr. McGregor’s garden? That’s certainly a possibility. Or did he bring her the heaviest diamond, one that was 200 carats? That’s a possibility too…but only if Benjamin Bunny has stock in Amazon. What do the other two words mean?

The rest of the story:

Answer: Caret is a wedge-shaped mark, the kind editors use to show an insertion of a word. Karat is a unit of fineness for gold equal to ¹/₂₄ part of pure gold in an alloy. Pure gold is considered to be 24 karats.

Many of these commonly confused words we are aware of and need only consult a good usage dictionary or reference book to verify. But what happens when we don’t even know such a word exists? I remember the first time I saw the word “ordnance.” I thought someone had made a typo and needed to insert an “i”—that is, until I learned that ordnance and ordinance are two entirely different words. Here is a sampling of other slippery homophones.

- advice – advise

- affect – effect

- bears – bares

- counsel – council – consul

- due to – do to

- kernel – colonel

- peak – pique

- principle – principal

- regimen – regiment

- site – sight – cite

- to – too – two

Ours is a tricky language, and spell check will often miss these problem words. So be sure to keep a good usage dictionary in one pocket and a good editor in the other.

QT 22 – Of Shoes and Ships and Sealing Wax (Part 2)

QT 22 – Video Transcript and Bonus Info

Today we pick up with Part 2 of our QuickTake on the serial comma. In Part 1, we defined the serial comma as the comma that separates the last two items in a series. For example,

Alice enjoyed tea with her new friends, Tweedledee, and Tweedledum.

This sentence tells us that Alice sipped tea with new friends (perhaps the White Rabbit and Humpty Dumpty), with Tweedledee, and with Tweedledum.

The Chicago Manual of Style, the authority for published works in the US, strongly recommends using the series comma, calling it a “widely practiced usage, blessed by Fowler and other authorities since it prevents ambiguities.” Those ambiguities include compound elements and appositives. An appositive is a noun or noun phrase that renames a nearby noun. For example, let’s drop the comma in our original sentence and see how the meaning changes:

Alice enjoyed tea with her new friends, Tweedledee and Tweedledum.

Punctuated this way—without the serial comma—the sentence tell us that Alice had tea with her new friends, who, by the way, are named Tweedledee and Tweedledum.

When asked, “What is the most frequent punctuation error that transactional lawyers make?” Attorney and lexicographer Bryan A. Garner responds, “Failing to use the serial comma (aka the Oxford comma). Its omission is a mistake in legal instruments because litigable ambiguities often result.” Examples of these ambiguities abound in the law.

Then why do some people believe it isn’t necessary? Perhaps it’s because journalists do not follow the Chicago Manual of Style. Instead, they follow the Associated Press Style Guide, which advises them to omit the serial comma—a rule thought to arise to save space and ink in printed copy. Check out any newspaper or magazine, printed or digital, and you will not find the serial comma. But AP governs only journalism. For the rest of us, economy is not as important as clarity.

There is one exception to the serial comma rule. When an ampersand is used instead of the word and, as in names of business firms and companies, omit the serial comma. So here, we would write,

The Law Firm of Alice, Tweedledee & Tweedledum

But when do we use the ampersand?

The rest of the story:

Ampersands are appropriate in notes, bibliographies, and tables. But be sparing in your use of the ampersand. It is not meant as an abbreviation for that very long word and.

In all other instances, be sure to use the serial comma. “No sentence has ever been harmed by a series comma, and many a sentence has been improved by one,” says Benjamin Dryer. For an enjoyable read on punctuation, check out Lynne Truss’s book Eats, Shoots & Leaves. (Notice the lack of the serial comma with the ampersand?) As she writes,

The reason to stand up for punctuation is that without it there is no reliable way of communicating

meaning. Punctuation herds words together, keeps others apart. Punctuation directs you how to

read, in the way musical notation directs a musician how to play.

Speaking of which, if you have a series (three or more words, phrases, or clauses), each item must be aligned grammatically with every other item, a grammatical form called parallel structure. So if A is an infinitive phrase, B must be an infinitive phrase, and C must be an infinitive phrase. Further, if the items have internal punctuation or form complete sentences, use a semicolon to separate the major groupings from the minor ones:

For breakfast, Alice preferred a soft-boiled egg, not too runny, not too rubbery; a compote of pears,

peaches, and cherries; and a slice of toast, slathered in butter and strawberry jam.

QT 21 – Of Shoes and Ships and Sealing Wax (Part 1)

QT 21 – Video Transcript and Bonus Info

Welcome to another 2-Minute Tuesday from Toolhouse Rock Studio. Today’s QuickTake with Cate begins with a stanza from a much-loved poem. You may remember it.

“The time has come,” the Walrus said,

“To talk of many things:

Of shoes—and ships—and sealing-wax—

Of cabbages—and kings—

And why the sea is boiling hot—

And whether pigs have wings.”

Or to put Cate’s spin on it,

“The time has come,” the teacher said,

“To talk of serial things:

Of shoes—comma—ships—comma, conjunction—and sealing-wax—

And the fact that, according to editor Dryer, only ‘godless savages eschew the series comma.’”

Yes, today’s is a hot topic, the serial comma (or series comma), sometimes called the Oxford comma or Harvard comma. It is the comma that separates the last and next-to-last items in a series. Whatever you call it, use it.

A series means three or more items. Those “items” include words, phrases, and clauses. Here’s an example of three clauses, also from Lewis Carroll’s poem:

Their coats were brushed, their faces washed,

Their shoes were clean and neat—

Although the last item in a series is usually connected with a joining word such as and, or, and but, it doesn’t have to be—as in the example just given.

Bryan A. Garner writes, “Whether to include the serial comma has sparked many arguments. But it’s easily answered in favor of inclusion because omitting the final comma may cause ambiguities, whereas including it never will.”

Consider this example: If I were to give you a grocery list and five bucks, how may items would you come back with?

Please buy me milk, cookies, macaroni and cheese.

You’d probably come back with a small carton of milk, a package of cookies, and a blue and white box that says Kraft Macaroni and Cheese.

But is that what I had wanted? Or is this what I wanted?

Please buy me milk, cookies, macaroni, and cheese.

So what’s the problem? Why is there resistance to including the serial comma? Tune in next time to learn the answer—and an exception to the rule—and thanks for watching!

The rest of the story:

When asked, “What’s the most frequent punctuation error that transactional lawyers make?” attorney and lexicographer Bryan A. Garner, replied:

“Failing to use the serial comma (aka the ‘Oxford comma’). Its omission is a mistake in legal instruments because litigable ambiguities often result.”

He argues that the reason for “preferring the final comma is that omitting it may cause ambiguities, while including it never will.”

And if you think the serial comma isn’t really such a big deal, check out these cases:

United States v. Palmer, 16 U.S. (3 Wheat) 610,636 (1818), in which Johnson, J, in his dissenting opinion, writes

“[M]en’s lives may depend upon a comma….”

Rex v. Casement, [1917] 1 K.B. 98 (1916) for an English example of life depending on a comma.

(The Elements of Legal Style, 2nd edition, Bryan A. Garner)

QT 20 – Begging Your Pardon about Begging the Question

QT 20 – Video Transcript and Bonus Info

Welcome to 2-Minute Tuesday and another QuickTake with Cate. Imagine yourself standing in the grocery store ready to pay for your carton of eggs. The cashier looks up at you and says,

“That will be 12 dollars.”

“But I’m buying only one carton of eggs,” you respond.

“Yes, but these are organic, keto, gluten-free, vegan, grass-fed eggs.”

How would you respond?

“I beg your pardon?”

“That begs the question.”

“That raises a follow-up question.”

If you say, “I beg your pardon?” you’re asking the cashier to repeat what she said, perhaps wondering if she meant to say 3 dollars and 12 cents.

If you say, “That raises a follow-up question,” the cashier would likely respond, “Which is what?”

You would then reply, “Why are organic, keto, gluten-free, vegan, grass-fed eggs so expensive?”

If the cashier replies, “Organic, keto, gluten-free, vegan, grass-fed eggs are expensive because they are organic, keto, gluten-free, vegan, and grass fed,” then—and only then—you could rightly respond, “That begs the question!”

The term “begging the question” has traditionally referred to a logical fallacy of presumption, known in Latin as petition principii. It is a fallacy that presumes the conclusion which is at question in the first place. That is, it cites as evidence the very thing it is trying to prove, for example, “Vegetables are good for you because eating them makes you healthy.” This fallacy is also known as a circular argument. The conclusion appears at both the beginning and the end of the argument, creating a circle.

Yet, you will often hear people use the phrase “begging the question” to mean, “that raises a question” or “that invites an obvious follow-up question.” Its original meaning has been repurposed from a logical fallacy to a simple inquiry.

Unfortunately, the use of begs the question to mean raises a question is so widespread that most dictionaries recognize this new sense of the phrase. Careful writers, however, will avoid sloppy wording as well as sloppy thinking. Avoid using begs the question unless you are pointing out a logical fallacy. Instead say, raises the question.

So the next time someone says to you, “Parallel lines never meet because they are parallel,” first say “I beg your pardon?” If they repeat what you thought they said, then you can rightly reply that such a claim “begs the question.”

The rest of the story:

Good writing is the result of good thinking. If our thinking is muddled, so too will be our writing. Be sure to watch out for these six other logical fallacies:

- Lack of objectivity. Seeing only the facts that support your views and ignoring any contradictory information.

Although half the surveyed counties expressed dissatisfaction with our current forms, a sizable portion find the forms satisfactory. Thus, we can proceed without worry. (You may be tempted to ignore the dissatisfied half instead of investigating the reasons for their dissatisfaction.) - Hasty generalization. Forming judgments on the basis of insufficient evidence or special cases.

Public relations strategy Z increased participation 12 percent in Los Angeles county. Let’s try it in Eureka. (Los Angeles and Eureka are vastly different counties.) - Hidden assumptions. Hiding a questionable major premise.

We are promoting our newest program in grocery store chains because we promoted our other program in grocery store chains. (What supports the assumption that both programs should be marketed in the same way?) - Either-or. Setting up only two alternatives without allowing for possible others.

We must open a new office by spring, or we will lose participation in the program. (Surely there are other ways to avoid losing participation.) - False causal relationships. Assuming that event A caused event B merely because A preceded B.

Participation increased 42 percent as soon as we simplified the application forms. (Something besides the simplified forms might have been responsible for or contributed to the increased participation.) - Personal attacks or appeals to popular prejudice. Attacking people (ad hominem) or sinking ideas you don’t like by chaining them to irrelevant but unpopular actions or ideas.

Bill mishandled the budget last year, so he can’t be expected to motivate his staff. (Bill’s accounting ability may have nothing to do with his ability to motivate staff.)

It’s un-American to impose government regulations. (Often regulations are unpopular, but they that doesn’t make them un-American—a failure to define terms, as well.)

QT 19 – The Hokey Pokey of Prepositions, Adverbs, and Phrasal Verbs (Part 2)

QT 19 – Video Transcript and Bonus Info

Welcome to Part 2 of prepositions. Our last QuickTake ended with a cliffhanger, right there in the post office! Was the man right? Did the post office employees need grammar lessons? Should it have been “Please turn off your cell phone,” or was the sign correct, “Please turn your cell phone off”? And what did Toolhouse Rock Cate do to quell the mass hysteria that ensured?

“Excuse me, sir,” Cate said, hiding behind her package. “There is no such rule. It’s perfectly fine to end a sentence with a preposition.” The man stared aghast. Folks craned their necks to listen. “More to the point,” Cate continued, “the word ‘off’ isn’t even a preposition here. It’s a particle.”

“A what ?”

That’s right, a particle—a small word that looks like a preposition, acts like an adverb, but is attached to a verb. These verb-particle combinations create phrasal verbs, for example:

Bring up, drop off, check in, look up, run into, listen in, and turn off, as in turn off your cell phone.

So all that hullabaloo in the post office over a preposition at the end of the sentence? That wasn’t even a preposition!

In other instances, what look like prepositions might be adverbs. Check out these three uses of “off”:

He grabbed the book off the shelf. (preposition)

The crook took off at the sound of the alarm. (particle)

The train was a long way off. (adverb)

That takes us to the Hokey Pokey! Bet you’ve never minded the “prepositions” at the end. Wait. Are those prepositions? Or are they particles, part of the verb? Or maybe adverbs?

You put your right foot in

You put your right foot out

You put your right foot in

Then you shake it all about

You do the hokey pokey

Then you turn yourself around

That’s what it’s all about

If only I’d sung that in the post office! What kind of looks would I have gotten then?

The rest of the story:

The answer to the Hokey Pokey song is that the italicized words are not prepositions, not particles, but adverbs!

Another tricky construction involves the word “to.” Often “to” functions as a preposition, as in “I walked to the store.” Prepositions begin prepositional phrases. Here the prepositional phrase is “to the store.” But the word “to” can also begin a verb phrase called an infinitive, as in “Dilly likes to sing.” How do you think the word “to” is functioning in this next sentence?

Dilly will sing as long as he wants to.

That man in the post office would no doubt announce loudly that “to” is a preposition, violating the rule that isn’t. But in this case, “to” begins an unstated infinitive:

Dilly will sing as long as he wants [to sing].

To wrap up: There is no rule against ending sentences with prepositions. Some words that look like prepositions are particles, forming a phrasal verb, and the word “to” if followed by a verb is not a preposition, but an infinitive.

Who knew going to the post office could be so educational!

QT 18 – The Hokey Pokey of Prepositions, Adverbs, and Phrasal Verbs (Part 1)

QT 18 – Video Transcript and Bonus Info

Today’s QuickTake begins with a true story.

A few days before Christmas, I found myself standing in a long line at the post office, waiting to mail my packages. After several minutes, the man in front of me turned to the woman in front of him and said loudly, “Someone needs to teach these people grammar!”

The woman followed his gaze to a sign on the counter. “Please turn your cell phones off,” she read. “Ohh, I see. It needs a comma after ‘Please.’”

“No!” the man shot back. “The sentence ends in a preposition. It should read, ‘Please turn off your cell phone.’”

Now before I tell you the end of the story, which sentence do you think is correct?

- Please turn your cell phone off.

- Please turn off your cell phone.

The answer is both!

What the man in the post office objected to was the word “off” at the end of the sentence, violating the rule, “Never end a sentence with a preposition.”

But—spoiler alert—there is no such rule!

Prepositions are words like on, at, of, into, from, with, to, about, for, up, and in—small joining words that show a relation in time or space between one object and another. In Latin grammar, writers could not end a sentence with a preposition, but “Latin grammar should never straitjacket English grammar” (Garner, MAU).

In English, we can and do end sentences with prepositions, for example,

You’re someone I can count on.

That’s something we should look into.

What is this made of?

What we want to avoid is awkward, stilted, or unnecessary prepositions at the end of a sentence.

Not “It is difficult to know about what you are thinking.” but “It is difficult to know what you are thinking about.”

Not “Where is she at?” but “Where is she?”

And some words that look like prepositions aren’t prepositions at all, but instead are adverbs, called particles. That’s where the Hokey Pokey comes in—but uh oh, looks like we’re out of time. Check back next time for Part 2 to learn more…and to hear the end of the story!

The rest of the story:

While grammar does not forbid prepositions at the end of sentences, good style might. The place of greatest emphasis in a sentence is the end, the last word packing a punch. Good writers don’t waste that position on weak words. Eliminate prepositions that add nothing to meaning:

- She could not help [from] smiling.

- The table is too near [to] the door.

- Let’s meet at [about] one o’clock.

- His house is opposite [to] theirs.

On the other hand, be sure to include necessary prepositions:

- A couple of books are missing. NOT A couple books are missing.

- They don’t stock that type of toaster. NOT They don’t stock that type toaster.

- What time does the bus depart from South Station? NOT What time does the bus depart South Station?

Also be sure to attach the correct prepositions in compound items:

- She has a great interest in, as well as deep respect for, rare coins.

Writers often omit the first preposition, creating grammatically incorrect sentences. Be sure to read each element separately to ensure the right preposition.

Check out a current reference book for more about prepositions, such as the Gregg Reference Manual or Chicago Manual of Style.

QT 17 – They’re My Contractions, Not Yours! The Perils of Possessiveness

QT 17 – Video Transcript and Bonus Info

Hey, everyone! Welcome to 2-Minute Tuesday and a QuickTake with Cate that has folks fighting over whose it is. Or is that who’s? When do we use apostrophes in words, and when don’t we? When is it its, and when is it it’s? When is it your, and when is it you’re?

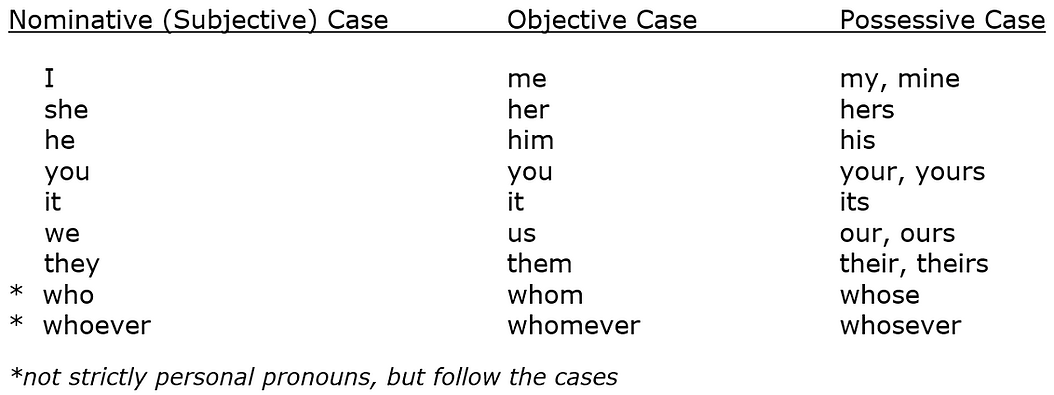

To crack the case, let’s begin with pronouns. Pronouns, which are noun substitutes, have three cases: the nominative (or subjective), the objective, and the possessive case. Possessive case pronouns show ownership—something belongs to someone. Notice that the possessive case pronouns already exist. We never have to add an apostrophe to them. That’s right: NEVER.

We would write, “The car lost its bumper when it spun out,” and “That painting is your best.”

So if the possessive case pronouns never need an apostrophe, what is the word it’s? It’s, with an apostrophe, is a contraction—the two words it is pulled together (or contracted), with a letter dropped out, indicated by the apostrophe.

It’s = it is

You’re = you are

They’re = they are

Who’s = who is

Other common contractions are can’t (cannot), won’t (will not), shouldn’t (should not), they’ll (they will), could’ve (could have), would’ve (would have). Take note: There is no such word as could of. Then why do people write that? Probably because when we say the contraction, could’ve or would’ve, we hear the sound of. But the contraction is formed from the word have, not of.

It’s easy to become confused. So be sure you’re proofreading and that your proofreading skills are up to par. And one more thing: Never, never use an apostrophe to form a plural! It’s lions, tigers, and bears, CDs and ATMs, Smiths and Joneses.

Taking a play from Dreyer’s playbook, “For a modest monthly fee, I will come to wherever you are, and when, in an attempt to pluralize a word, you so much as reach for the apostrophe key, I will slap your hand.”

The rest of the story:

Some contractions can have more than one meaning. Consider these examples:

- What’s his name? (What is his name?)

- What’s she do for publicity? (What does she do for publicity?)

- What’s been going on? (What has been going on?)

- When’s the last time he visited? (When was the last time he visited?)

- Let’s look for the bus. (Let us look for the bus.)

To avoid confusion for your readers, consider writing out awkward contractions. Also be aware that adding an apostrophe s to a noun might trip up your reader. Consider these two examples:

· Mr. Roker’s coaching has resulted in a winning season.

– Mr. Roker’s is a possessive form.

· Mr. Roker’s coaching his team on free throws.

– Mr. Roker’s is a contraction for Mr. Roker is, but it could be initially misread as a possessive form.

It’s better to write out the two words: Mr. Roker is coaching his team on free throws.

Test yourself in the sentences below. Do we need the possessive form or the contraction? Answers below.

- The truck landed on it’s/its roof.

- Its/It’s not unusual to hit triple digits in May.

- The tornado uprooted every house except there’s/their’s/theirs.

- There/They’re/Their excited about their upcoming vacation.

- The coat belongs to the woman who’s/whose dog ran away.

- Whose/who’s coming to the party?

- I wonder what you’re/your lottery ticket numbers are.

- Your/You’re bound to win.

If you’re still having trouble, consult a good grammar book or university website for more exercises, such as The Gregg Reference Manual or A Writer’s Reference.

(1) its (2) It’s (3) theirs (4) they’re (5) whose (6) who’s (7) your (8) you’re